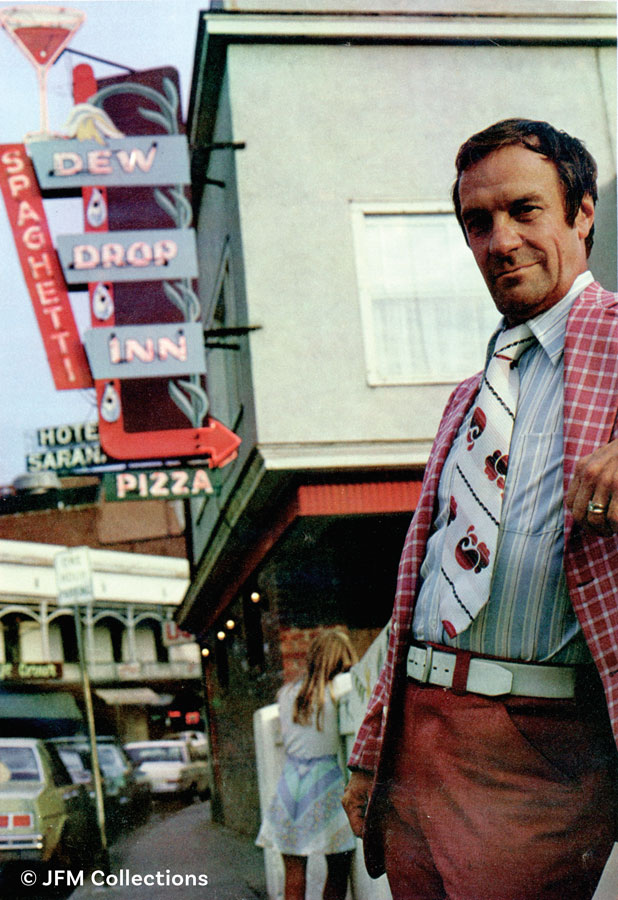

He was Marvelous Monty, Hollywood’s “gift to golf.” Tall, dark and charming, he was a big teddy bear of a man always good for a game or a gamble. He hit the longest drives in the world and lowered the course record at a Palm Springs golf course four days in a row.

Mysterious John Montague came to fame in the closing days of Prohibition. He was a West Coast sensation, a friend of the famous. He reportedly once pointed to a bird on a wire and proceeded to knock it off with a hard-driven ball.

He was photographed beating Bing Crosby in a round of golf. Bing was playing with woods, irons and putter; Monty wielded a garden rake, spade and fungo bat. As Golf Magazine tells it, Crosby conceded the match after Monty made birdie in three strokes on the first hole of the Lakeside Country Club, outside Los Angeles.

Inside Golf magazine sent sportswriter Grantland Rice west to see Montague play and, upon his return, he wrote, “The winner of the 1936 Amateur Championship will not be the national champion for the simple reason that John Montague is not entered.”

While West Coast celebrities were having fun in the sun, back East the Adirondacks was a hotbed of bootlegging. Until the repeal of Prohibition, in 1933, state troopers were kept busy patrolling the back roads of the North Country, a runway for rum from the Canadian border to Lake George. Bootleggers became familiar with all the roadhouses along Route 9 as they drove their wet wares to market.

In the early hours of August 5, 1930, three masked men entered the restaurant of Kin Hana, by the Stickney bridge on Route 9 in Jay. The Hana family lived in the same modest building. Hana had come to America from Japan as a cabin boy. He was left behind in New York when he fell ill and the ship sailed.

Somehow, Hana had attracted the attention of Harriet Ropeson, of Au Sable Forks, who sent him to cooking school. On his return, he married Elizabeth Cobb and opened a series of restaurants.

On that summer night, as the family was closing the place, Mrs. Hana first thought the masked intruders “were friends from Keene playing a joke on her,” reported the Essex County Republican. Then she saw their guns. They forced her to open the safe and took between seven and eight hundred dollars. As they were leading her into a back room, her father, Matt Cobb, woke and grappled with one of the robbers, who hit him with a gun and tied him to his bed. As the men retreated to two getaway cars, Cobb wormed his way loose, jumped out a window, ran around the building and attacked a bandit posted as a lookout. But the men beat Cobb into submission, tied him up a second time and left him lying on the ground.

The four men drove away at high speed. Heading south on Route 9, they passed two troopers on routine booze patrol. Sergeant McGinnis and Trooper Wood made a quick U-turn to pursue the vehicles and managed to bring one car to a halt. As the troopers got out of their car, the bandits turned around and headed back toward Jay. They went flying off the road opposite the Tobey Homestead, the handsome brick building just beyond the Baptist Church in Jay, and crashed through a guardrail and down the embankment, killing the driver.

The deceased was later identified as John Sherry, of Utica, a man with a long criminal record, according to newspaper stories of the time. The other person in the car was William Carleton, also of Utica, whom Mrs. Hana identified as the one who had forced her to open the safe.

In the car troopers discovered two guns and more than six hundred dollars. They also found a Gladstone bag and golf clubs belonging to a man named LaVerne Moore. Moore was well known in Syracuse, his hometown, as a gifted athlete and a prankster with a mean streak. A Syracuse University football coach thought he had all-American potential and offered to pay his way to Dean Academy to prepare him for college football. Moore was also famous for his golfing exploits and his pitching prowess. On a trip to Florida, he became friends with Babe Ruth after trying out for the Yankees and, on a dare, pitching to the Boston Braves.

As a young man in his late teens and early twenties, Moore’s darker side showed in pranks he pulled, as told by Joe Ganley, a columnist for the Syracuse Herald American. Early one morning, Ganley reported, three pals of Moore’s hopped into his big Caddy for a late-night spin in the countryside. On the way up a hill, the car “came to a bucking stop, making loud noises.” Moore suggested the passengers get out and push the car over the brow of the hill. When they did, Moore drove off, leaving his pals stranded in the country at four a.m. Moore would deliberately drive over hats that had blown into the street, Ganley said. He would offer old men waiting for streetcars a lift home, then scare them by driving around the block at a terrifying speed.

On the positive side, Moore had once pelted a group of Ku Klux Klan members with rotten tomatoes. As for golf, Ganley didn’t believe Moore ever knocked a bird off a wire, but he acknowledged that Moore was famous for the length of his drives.

When he was twenty-five Moore left Syracuse for parts unknown; it was 1930, the year of the Hana robbery. By 1937 Syracuse police began to suspect that Marvelous Monty, the golfer of Hollywood fame, was LaVerne Moore, whose clubs had been found, along with a dead man, in a getaway car in Essex County.

Montague avoided having his picture taken, but eventually a hidden photographer managed to catch a snap, which was published. Syracuse police notified Essex County authorities that Moore and Marvelous Monty were one and the same. Roger Norton, the driver of the second car, had surrendered to police in 1930 and was prepared to testify that Montague was the fourth man in the robbery. But the other robber, William Carleton, denied it. Montague admitted he was Moore (he’d legally changed his name) but denied taking part in the robbery.

Hollywood celebrities like Bing Crosby and funnyman Oliver Hardy sent petitions to the governor of California opposing Montague’s extradition. But, in the end, Montague willingly came east by train, accompanied by two New York State Troopers. When the train stopped in Saratoga Springs, Crosby, who was taking the waters there, came to the station to wish Montague well.

Inside Golf reported that Montague, after his indictment and while free on bail, played a round of golf at the North Hempstead Country Club, on Long Island, with Grantland Rice, popular author Clarence Budington Kelland and the famous golf teacher Alex Morrison. Montague “burned up the course with a remarkable 65,” Golf Magazine stated, “breaking par by five strokes and never taking more than two putts on any hole.”

In Elizabethtown, Montague was treated as a celebrity. The New York Times sent star reporter Meyer Berger to cover the four-day trial. A panel of male citizens was picked for the jury, but it was predominantly women who filled the spectator benches. Monty’s charm was such that Essex County jailers allowed him to take a walk around town on his birthday and stop for a soda at a drugstore. He smiled and talked with townspeople.

Before the trial, District Attorney Thomas W. MacDonald spoke confidently of the outcome, saying that Norton and Carleton had been convicted on far less evidence. But neither Matt Cobb nor any member of the Hana family was able to positively identify Montague.

Montague’s gray-haired mother and Francis McLaughlin, a newspaperman from Washington, D.C., testified that he was at home in Syracuse at the time of the robbery, undermining the D.A.’s case. On the stand, Montague admitted to being in Essex County with Carleton earlier that day but insisted that McLaughlin had driven him that evening to Syracuse. His mother and his two sisters testified that Montague was home by midnight.

The jury deliberated from six to 10:45 p.m. on Thursday, October 28, 1937, and returned with a verdict of not guilty.

“Gentlemen,” said Judge Harry E. Owen, “this verdict is not in accord with what I think you should have returned. That, however, is up to you, and not to me.”

When Montague was released, among the young ladies lined up seeking his autograph was the niece of Sheriff Percy Egglefield and the daughter of Judge Byron Brewster.

Montague spent the night at the Deer’s Head Inn and was whisked away by friends the next day.

Was Hana’s background a factor in the trial? In 1937 newspapers were filled with anti-Japanese stories, and headlines screamed of the invasion of Shanghai. The Hanas’ daughter, Harriet Hodges, was a child at the time. But in a recent telephone interview, she remembered it clearly. Hodges doesn’t think anti-Japanese sentiment played a part in the verdict. For her, the most disturbing thing about the robbery was that Roger Norton, driver of the second car, was a family friend. “We knew his wife. He often stopped at the restaurant,” Hodges said, “and ate dinner with our family.” Montague soon showed up in New York City. It was said that Bing Crosby’s brother Everett was going to sign him to a movie deal, and other hot offers were on his plate. Monty denied all such rumors. He did get together with his old baseball buddy, Babe Ruth, the great female athlete Babe Didrickson and local golf champion Sylvia Annenberg for a charity event at Fresh Meadow Country Club, on Long Island.

The New York Times estimated that ten thousand people showed up for the event. The celebrity golfers were mauled by the crowds as they tried to play. Police called the match at the halfway mark, afraid that people would get injured in the crush.

Montague returned to the West Coast amid stories that he would play in a golf championship in the Philippines and act in the movies, possibly in a film about Paul Bunyan. But the moralistic Hayes Code was in force in Hollywood, and it seems that, despite Montague’s acquittal, the trial blighted his career. At least part of the public agreed with the judge that the verdict did not match the evidence. When Montague was hurt in a car crash in Los Angeles in 1955, an Essex County Republican headline blared, “Montague, hurt in crash, one of 4 who held up Hana Place.”

In 1938 Montague’s Christmas card revealed he had married Esther Plunkett, a well-to-do Beverly Hills matron who had attended the Elizabethtown trial. The couple were living in California, where Monty played only an occasional game of golf.

After Plunkett’s death, in 1947, Montague’s life took a turn for the worse. Whatever money he possessed trickled away, and photos of the period show him on the golf course, weighing three hundred pounds, looking gray and grizzled. He lived quietly until his 1972 death in a motel room in Studio City. In the 1980s rumors circulated that Jackie Gleason would star in a biopic of Montague’s life. But, like many Monty stories, it never happened.